Within Tai beliefs, the Pee Suea (butterfly) symbolizes a lingering fragment of the soul or the spirit of an ancestor

There was a period in my life when I felt as though part of me had disappeared. Not in a metaphorical sense, but viscerally — as if fragments of my being had scattered, leaving me unable to fully recognize myself or move through the world with the wholeness I once knew. I was diagnosed with Panic Disorder, a condition that disrupted not just my body but the very foundation of how I understood my own existence.

The attacks came without warning. My heart would race, my breath would shorten, and suddenly I was no longer grounded in the present moment. It was as invisible threads that held me together had snapped, one by one. Medical treatment helped manage the symptoms, but there remained something deeper that medication alone couldn’t address — a profound sense of fragmentation, of being somehow less than whole.

It was during this time that I turned to the traditional Lanna practice of “Bai Sri Su Khwan”. Being born and raised in Chiang Rai, the northernmost province of Thailand and part of ancient Lanna, this ceremony has always been close to my heart. It aims to call back one’s Khwan, or viral essence. Sitting there, surrounded by the soft glow of candles, the rhythmic chanting of prayers, the gentle binding of sacred threads around my wrists, something shifted. Not dramatically, not immediately, but subtly. It wasn’t that the ceremony “cured” me in any medical sense. Rather, it provided a language that served as a framework for understanding what I was experiencing as the feeling that something essential had fallen away, and the possibility that it might be called back.

This experience planted a question in my mind that would grow into an obsession:

What is that we lose when we feel broken? And how do we find our way back to ourselves?

Body as Archive

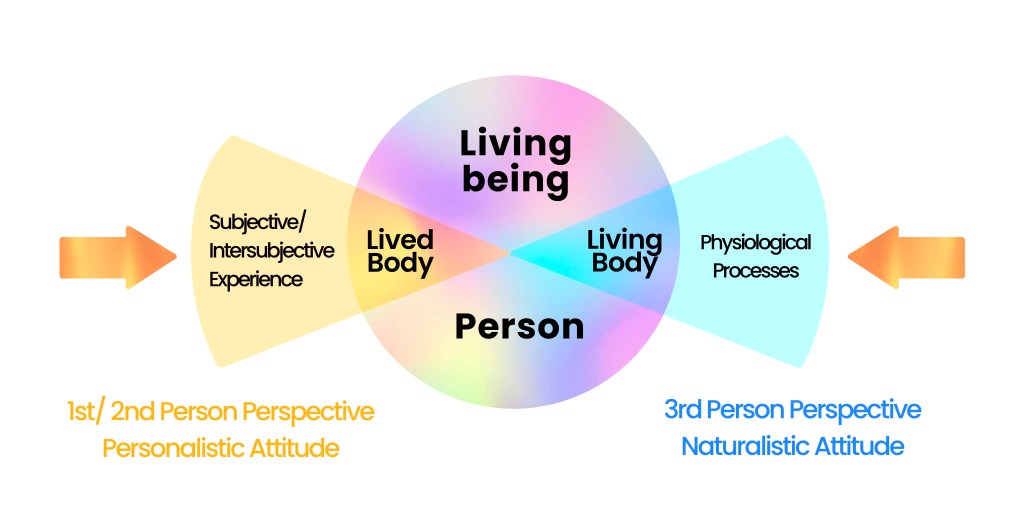

Merleau-Ponty’s philosophy: Corps Propre and Being-In-The-World

As I began to recover and reflect on my experience, l became aware of how profoundly the body remembers what the mind tries to forget. My panic attacks weren’t just psychological event — they were inscribed in my muscles, my breath, my heartbeat. The body, I realized, is an archive. It records fear, grief, joy, and connection in ways that don’t always translate into conscious thought.

This realization resonated deeply with the words of philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty, who described the body as the “Corps Propre and Being-In-The-World”, an archive of both concrete and intangible experiences. My panic attacks were not just psychological; they were inscribed in the very system that navigates reality.

This understanding is further validated by the theory of Embodied Cognition, which posits that memory is not solely housed in the brain, but is distributed throughout the nervous system, muscles, breathing, and automatic responses of the body. Pioneering work in somatic trauma therapy, such as that by Bessel van der Kolk (2014), clearly shows that the memory of traumatic experience is stored not as narrative, but through physical sensation and reactivity. This helped me understand that my body was “narrating” something that I had never truly listened to.

When my heart suddenly raced in the middle of an ordinary day, it wasn’t responding to present danger but to echoes of past trauma, to memories stored not in neural networks alone but in the very tissue of my being. The tension in my shoulders, the shallow quality of my breathing—these were footnotes in a history written by the experience. This rapid, automatic responses aligns with neuroscientific findings by researchers like Gray & McNaughton (2000) and LeDoux (2015), which show that the neural systems governing fear perception often operate faster than conscious reason. The feeling always precedes the thoughts.

This realization resonated deeply with what I was learning about Khwan. In Tai ethnic groups’ cultures, the concept of Khwan isn’t simply spiritual folklore but it’s a sophisticated understanding of how human beings exist as integrated systems of body, emotion, memory, and spirit. When someone experiences shock, illness, or profound loss, their Khwan — these vital particles of life force can scatter or flee. The person continues to exist physically, but something essential is missing. They move through the world diminished, unable to fully inhabit their own life.

the beauty of this framework is that it doesn’t separate mind from body, emotion from physically. It recognizes what Western medicine is only beginning to fully acknowledge that trauma lives in the body, that healing requires more than treating symptoms, and that our sense of self is fragile, requiring care and ritual to maintain.

Khwan: The Invisible Network That Holds Us Together

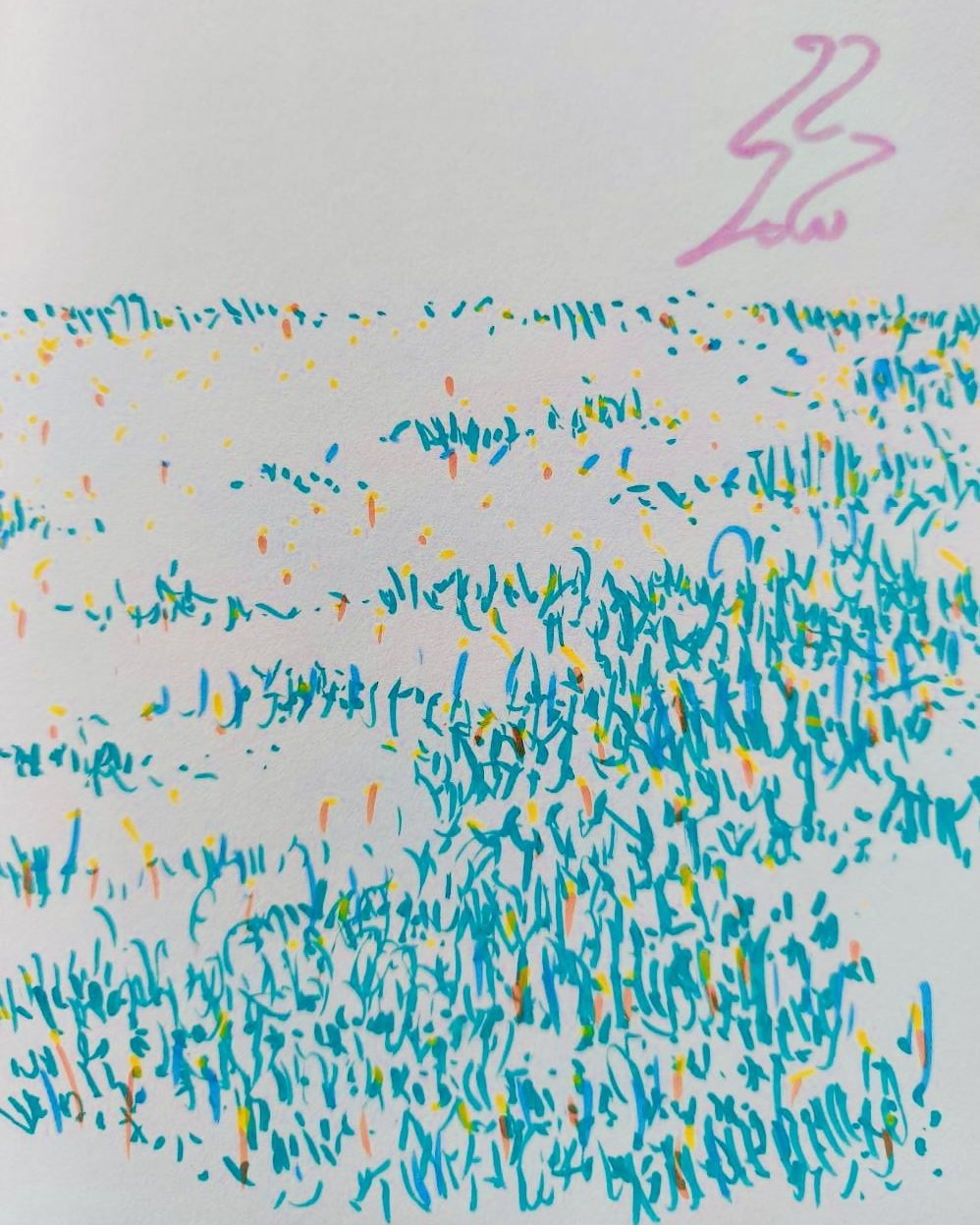

My concept sketch exploring Khwan in Tai culture

According to Tai ethnic groups’ belief systems which span from Yunnan in China through Southeast Asia to what James C. Scott calls Zomia, human beings possess multiple Khwan (ຂວັນ, ขวัญ). The most common teaching speaks of 32 Khwan, though some groups believe in as many as 80 to 100. These aren’t arbitrary numbers but they represent the understanding that we are not unified, indivisible selves, but rather complex assemblages of vital forces, each connected to different aspects of our being.

What struck me most about this concept is how it contradicts our modern notion of the self as a singular, bounded entity. In Khwan philosophy, we are fundamentally relational beings. Our Khwan connects us not only to our own bodies but to our families, communities, ancestors, the land we live on, and forces beyond ordinary perception. We exist not as isolated individuals but as nodes in a vast network of relationships.

This helps explain why the ceremony that brought me comfort worked the way it did. The Bai Sri Su Khwan isn’t just about an individual recovering their scattered essence, it’s about restoring broken connections. The threads tied around my wrists symbolized these connections being rewoven. The prayers spoken weren’t just for me but they also invoked relationships with ancestors, with the community gathered around me, with forces both seen and unseen.

When Khwan falls away whether through fear, illness, or separation — it’s not just an internal crisis. It’s a rupture in the web of relationships that sustains us. And healing, correspondingly, isn’t just an individual journey. It requires the participation of others, the acknowledgment of our place within larger systems of meaning and care.

What moved me most about the Su Khwan ceremony wasn’t any supernatural explanation but the recognition that healing requires ritual, symbol, and community. Modern medicine treated my panic disorder with medication and cognitive behavioral therapy — both helpful and necessary. But the ceremony offered something different like a symbolic language for processing what I’d experienced, a way to mark the transition from fragmentation to reintegration.

The act of binding threads, of sitting together, of hearing one’s name called in prayer — these weren’t medical interventions, but they were powerful nonetheless. They were ways of saying: you matter, you are connected, you belong, your wholeness is important to us. This resonated powerfully with the idea of “Trauma as a Public Feeling,” as proposed by scholar Ann Cvetkovich. Her work suggests that pain is not merely a private, individual matter, but a social phenomenon that requires a public space for acknowledgment and healing. The Su Khwan ceremony thus acts as a necessary public ritual, restoring the communal ties that trauma had severed. In a world that often treats illness as a private, individual problem to be solved efficiently, this felt revolutionary.

I began to understand the ceremony not as a literal calling back of spirits but as a “language of relationship” which is a way of acknowledging rupture and intentionally working to repair it. The threads weren’t magic; they were reminders. The prayers weren’t supernatural interventions; they were attestations of care and connection.

This reframing helped me see that healing isn’t about returning to an original, perfect state. It’s about acknowledging what has been lost or broken and then deliberately, patiently, reconstructing a sense of wholeness that incorporates that brokenness. The goal isn’t to erase the experience of panic and fragmentation but to integrate it, to find a new configuration of self that includes what I’ve been through.

Leave a comment